One of the three investors in Nigeria’s Backward Integration Plan on sugar, BUA Sugar Refinery has allegedly been shortchanging the Federal Government to the tune of billions of naira, which the company enjoys as concessions on import duty and levy for raw imported sugar, by not producing an ounce of sugar since the BIP was initiated, findings have revealed.

BUA’s performance in the BIP already rated as poor and unacceptable by the National Sugar Development Council after the initial 4 years of BIP implementation continues to dip by the day, but its import quota on the other hand is rising, as the company appears more focused on importing raw sugar for its refinery which has been expanded recently.

In 2020 BUA got a 360,000mt presidential quota allocation, out of which it utilized 313,700mt and has now applied for 600,000mt import quota for 2021, without a complementary investment in backward integration, which is a pre-condition for enjoying increased import quota under the concessionary tariff.

At the end of the First Phase of the NSMP (2013-2016), BUA reportedly raked in N66.5billion profit from accrued tariff concessions and ploughed back only N9.3billion out of that into the BIP, a far cry from other investors who channelled a minimum of 50% back into the BIP.

Despite a 2017 radical review of the entire BIP strategy as well as the entire reward and sanction regime of the National Sugar Master Plan, which has placed emphasis on cultivation, jobs creation and local manufacture as a pre-requisite for quota allocation, BUA is yet to produce sugar locally like other stakeholders in the industry.

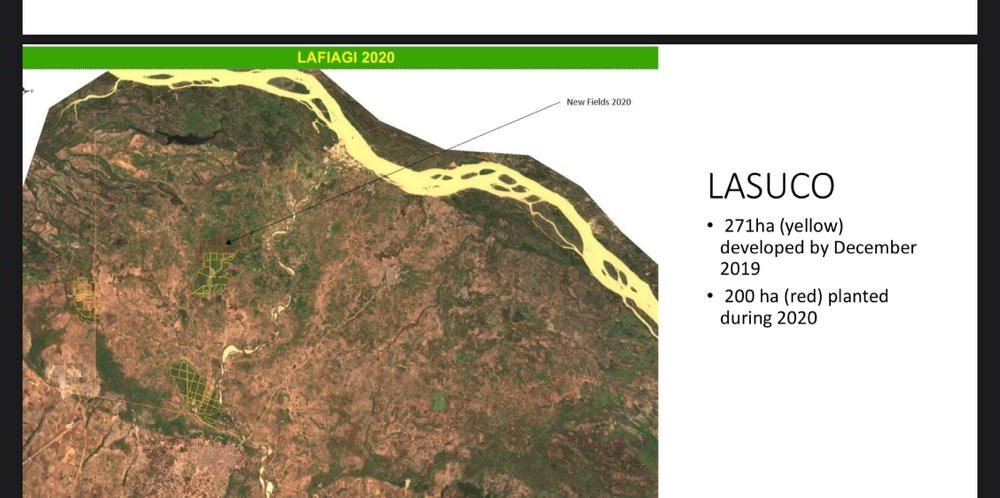

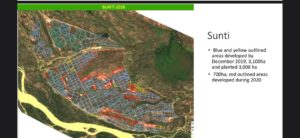

Cumulative Satellite monitoring data obtained from an anonymous source in the NSDC shows gross discrepancies between the self-reported performance figures (amount of land cultivated for sugar cane) by BUA’s Lafiagi Sugar Mill with what is actually on the ground verified by the satellite imagery.

BUA claims to have developed 6,500ha of land by May 2020 with 2,220 ha cultivated with sugar cane, however satellite images show that since 2016 only 473ha were developed and cultivated, despite enjoying billions in concessionary rights Nigerians are yet to see or have a taste of BUA sugar. A sugar factory without sugar cane represents a smoking gun for the Federal Government to investigate.

A 2015 dated letter from the NSDC shows that BUA was slammed a suspension from enjoying the privileges of tariff concessions for failing to follow the examples of productive backward integration programs under the Nigeria Sugar Master Plan. Where other stakeholders were in re-investing profits from the tariff concessions into local sugar factories, BUA sugar rather was investing in the building of a new import-driven refinery in Port-Harcourt in flagrant disregard of the suspension of further sugar efinery development in the country.

What the country clearly needed at that time according to NSDC was an investment in sugarcane to sugar production to move the country out of its dependence on sugar imports, save foreign exchange and create jobs for Nigerians.

In another letter BUA was also denied an additional quota for raw sugar imports to service the new Port-Harcourt refinery by the NSDC, citing the need to protect the policy that was put in place to halt import dependency while stimulating investments, such as would harness the nation’s natural endowments for production of sugar from sugarcane.

The council also chided BUA for failing to demonstrate the level of commitment expected of him to justify the incentive being enjoyed from the federal government.

How the suspension after 2015 was lifted is still shrouded in mystery, as there has been no demonstrable commitment from BUA to drive the BIP, aside from projections and future dates of production, while it currently continues to enjoy tariff concessions on imports and has requested a quota increase from 313,700mt in 2020 to 600,000mt in 2021.

you

you

Given the gravity of infractions from BUA and seemingly no penalty from regulators, would-be investors would be right to assume that there is no level playing ground in the BIP initiative.

The policy still has room to accommodate more private sector players that can ultimately turn the table from importation of raw sugar to local production, to self-sufficiency and net exporter of sugar if the government can show that it is carrying out its regulatory oversight function without fear or favour.